PNGAA Library

An Australian Army concert party in the islands: Ed Zanders

Historical accounts of the exploits of Australian Armed Forces in New Guinea during World War Two have concentrated mainly on the fighting units, for obvious reasons given their bravery and sacrifice in battles with the Japanese. Perhaps less well known is the role of the army entertainment units that were established to boost morale among the troops in all the theatres of war. My father, Douglas Zanders, was a pianist in one such unit, the 3rd Australian Division Concert Party, which toured Queensland and the Northern Territory from 1942 onwards. In 1945, his unit was renamed Detachment No. 5, 1st Australian Entertainment Unit, and sent on tours to the Wewak area in New Guinea and to New Britain, where their last concert was given in January 1946.

The band, with Douglas Zanders on piano

Background to the Islands tour - April 1945 onwards:

The 3rd Australian Division Concert Party had been touring Australia since 1942 and had returned to Pagewood, Sydney, in early 1945 to regroup as the Detachment No. 5, 1st Australian Entertainment Unit. It was time to entertain the troops on the Islands. Their first port of call was the Wewak-Aitape area on the northern coast of Papua New Guinea. Aitape had been occupied by the Japanese from 1942 until its recapture by the Americans in 1944. The Australians had then taken over and moved towards Wewak to destroy the remnants of the Japanese 18th Army. Wewak was finally taken in May 1945, but fighting continued in the area until the end of the war some months later. The Concert Party tours appear to have been a success judging by the newspaper cutting shown here:

To Jacquinot Bay, New Britain, September 1945

The following description of the Party’s final months in New Britain comes from the personal memoirs of my father’s friend and colleague, Corporal Frank Lamprell, an entertainer from Melbourne.

‘Off we sailed next day and on the Tuesday drew in to Jacquinot Bay, New Britain. I must say the first impression of this place was very favourable. We had been told by Jack Sparkes, who had been there before, that it was a woeful dump, but how wrong he was. We could see at once it proved to be the best spot of our entire tour. The sisters and nurses disembarked for 118 AGH, which had come from Aitape to Jacquinot Bay, then we followed and got in to a truck and were driven along a palm lined road for about a half mile where we got out to be billeted with an ammunition unit. Bully beef and M and V were the main meat dishes with fish patties in close second; I nearly starved, but the area was so beautiful I would have willingly lived on tea and biscuits. We were right on the edge of the Bay itself, there was no beach and swimming had to be a cautious event, as sharks were often seen close to the shore. Small boats, lakatois, sailing boats and skiffs were to be found everywhere, abandoned by troops who had move out, so our boys grabbed what they could and repaired them, painted them gay colours and had much fun paddling around the Bay. In fact Sunday was very similar to Frankston or Mornington on the same day, only these resorts could never have the same colourings of the sea, sky and mountains which changed every few minutes; the sunsets were really magnificent.

Our camp was set in what had once been a coconut plantation and everyone had to be careful to walk along the paths and not under the trees as nuts falling could kill a man: we saw several natives horribly crippled who had been struck on arm, leg, thigh or shoulders when young. Trembles were very prevalent, as the nearest volcano was at Rabaul ninety miles away, and the sight of the light globes swaying or beds vibrating became a common occurrence. One night we saw a flare in the sky and were told it was an active volcano very far away; it looked very fierce. At 118 (AGH) were several nuns, Dutch, German and Australian who had been brought from Rabaul for rest and treatment after Jap domination. Priests were there too, but while they were all very weak and ill, the nuns seemed to be very vigorous and well. Indian POWs were there too; the hospital had much trouble with these, as when beans were served, great care had to be taken that no pork was left behind. These Indians were terribly emaciated; one who died weighed only three and a half stone.

A couple of special concerts were presented to the nuns by Douglas, Don, Slim Jim, Ted and band, with Don creating a sensation by playing and singing German music and songs, Bach, Beethoven, etc. The nuns had heard no music for three years; one had never seen a saxophone. We gave a show at the New Zealand Air Force about two miles away. They were most kind to us, nothing too much trouble for them and a really splendid audience too. Don became very friendly with two of the lads who were cooks in the Officer’s Mess and they were always coming down taking two or three of us back for tea where we would feast on pork, roast onions and potatoes, green peas, stewed fruit, ice cream, etc., food the Aussie troops never ever saw. On another occasion a couple of native lads came along as Jumbo was busy practising his trombone; they were looking down wondering where the noise came from. Jumbo could hardly blow for laughing. Then we got them to sing; one was rather timid, but the other obliged in a high loud tuneful voice with a song that seemed to be endless. On another occasion Don asked the native to sing one of their native tunes and out came Lily Marlene!

At one point we handed all our steel helmets in to the right quarter, had them marked off on hooks, then were given them back to toss into the sea as the authorities didn’t want them. So we had a gay time throwing them into the Bay.

The coral beds were an endless source of delight. Douglas took me out in a small boat one day and I was amazed at the lovely colouring and clarity of sea and coral. Jacquinot Bay was fast becoming an empty area. Over the bay we could daily see the fires lit by natives who were detailed to demolish and burn the deserted camps.

Troops became fewer and fewer, and ships now went down to one or two a week then one a fortnight. One Sunday morning Douglas came running up to say that I had to be packed and at the airstrip by 9.30: half an hour to go! Douglas packed my gear and we trucked it to the airstrip with ten minutes to spare—then had to wait an hour and a half for a plane! We got weighed in, etc., then off we went to the last stage of our tour, Rabaul, little dreaming that only a few days later there was to be a terrible air disaster in which the entire personnel were to be killed in such a wild area that it was impossible to bring the bodies back; they had to be buried on the spot.

By plane to Rabaul

It was a beautiful day for our trip and, though passing over the jungle and mountains was a bumpy business, the sea view was marvellous. We could see the coral reefs under the water, also sunken boats and barges, while the white waves running in and off the sands were really lovely to see. Rabaul in sight, we passed over two volcanoes, one extinct with trees and shrubs growing inside, but the other a nasty looking affair with smoke belching from it. This was the one that caused all the bother a few years previous and caused a mass exodus to Moresby. Circling over Simpson’s Harbour preparatory to landing we could see dozens of sunken ships under the water or with masts protruding while the shores of the harbour were crammed with damaged craft of every description, with the wharf a ruin, hastily patched here and there to facilitate movements.

Making a beautiful landing on the dusty strip we were not allowed to unload our own gear, Japs were on hand to do that for us. The strip was right under the volcano that was naughty and a strong odour hung in the air, this was for ever present sometimes worse, sometimes milder, but there it was real sulphur smell and some days it was heavy carbide: it made us all very heavy handed and sleepy. We passed damaged pill boxes and fortifications, ruined trucks, tanks, shell holes and what have you, past ANGAU HQ where the ANGAU boys put on a marvellous show in their smart 50-50 uniforms consisting of jungle green shirt, short laplap and webbing. Their drilling under their own NCO was a sight to see.

Jungle vines and vegetation had been cut away to make a path for the traffic and, here and there, asphalt and kerb stones stood out from the debris. Not a building stood, everywhere could be seen concrete floors, some covered over, others in process of being built on, the only standing wall was at the ex-office of Burns Philp Shipping Company, but even this wasn’t a solid wall, having a large opening where a door had once been, plus several window openings.

Rabaul is set under the shadow of hills that come down to about a quarter mile from the water’s edge. These hills are heavily covered with vegetation and are honeycombed with caves and tunnels carved out by the unfortunate POWs under the Japs. Most of the caves were found to be filled with radios, cars, machinery and ammunition, also large maps of every city, port, bay and harbour in Australia, in detail. Mounds of earth with tiny vents were really Jap strongholds and these were everywhere, while in many places the ground shook empty under us as we walked over underground hideouts.

We were in a pawpaw plantation with ripe juicy fruit, ours for the plucking, and a huge frangipane tree hung almost over our tents, its heavy fragrance almost obliterating the stench from the volcano. There were a lot of tropical trees and plants in bloom, hibiscus, lilies and a lot of names I can’t recall, didn’t know in fact. Several trees had pieces of corrugated iron, pieces of metal, etc., stuck in their trunk some high up, and some hanging very precariously, having been blown there by bomb blast. If anyone happened to be passing when one of those pieces fell, well why talk of such things now that peace is here? After tea we made a tour of the area and saw the pier at close quarters also the remains of what had once been a fine baths, swimming pool, gardens combined.

hen extra troops came in, dozens of tents were erected and the camp lost its neat appearance, battered marquees, leaky tents, anything that could be utilised was put up and the lads bore it bravely; anything was good enough, they were going home for good! When I awoke in the morning after we reached Rabaul, I found hundreds of Japs running everywhere, doing all the odd jobs about the camp. All were in the charge of their own NCOs and at lunch time gathered and ate special food brought in from their own compound. For the first few weeks it was a common sight for every Jap, whether on foot or in truck, to salute us smartly, but this eventually fell away, although they were supposed to continue with it. The Jap compound was built about a half mile away to the left of GDD and all Japs were returned to their camp by 6 o’clock, were in bed by 8pm, up at 3.30am and ready for the road at 5.30am.

On the right of GDD was another compound built for the war criminals which was brilliantly floodlit by night. One blanket was all we needed at night in Rabaul. The Chinese community were housed in grass huts in their own compound near the town, also nearby was a native hospital, out of bounds to all troops; the rule had no need to be issued. Near the picture site assigned to our area were the remains of what had once been a Chinese cafe, and huge piles of broken crockery bore testimony to the blast of the bomb. Turning over the wreckage with the tip of my boots I came across one saucer completely unscathed, plus three tiny plates and one cracked tea cup which I used as a shaving mug till I left Rabaul.

The road to Kokopo was most rough, but interesting, passing several Australian camps, then around a narrow road that ran between the sea and the cliff where Jap trucks had to draw close to the cliff to allow us to pass. Thousands of naked and semi-nude Japs swarmed everywhere, on rocks, battered boats, or in the huge caves carved out of the cliffs and in which they lived. Barges, which were drawn out of the sea in to the caves when air raids were imminent, were to be seen in profusion. Some in the caves had been trapped half way in and blasted in two. We had to pass an Australian guard who opened a gate for us and on we went, passing Chinese camps, where inmates waved furiously so that we would know that they were not Japs. The Indian camp was most interesting, I would have liked to have poked around a bit, but of course we could not stop; besides, the magnificent Ghurkha guards did not look very friendly to visitors.

After lunch we had a look see around the area: a stone jetty was of interest with a battered ship at its end; this ship was said to be the first ship hit in the war. Some of us climbed an incline to the ruins of what had once been a beautiful building but was now a shambles. The bath room had been blue and pink tiled, kitchen and lavatories were white tiled, there were huge underground tanks and a concrete pillared veranda overhung with flaming tropical creepers. It really must have been a lovely spot and obviously a planter’s home. Imagine our surprise to hear that it had been the number one brothel of Rabaul!

We were to show in the open and had to wait until the sun had moved off the spot chosen, which was ideal under trees and on a grassy sward. A priest, several nuns, an army woman doctor, plus thirty native novices and as many children, all arrived for the show; priests, nuns and doctor coming by jeep, the others crowding in to open trucks. The novices wore no shoes but grey dressed and white veils the children all were dressed in neat fresh print dresses complete with ribbons in their hair and handkerchiefs in hand. They were all most enthusiastic over the show, the novices burying their hands in their faces to hide their laughter while the nuns were bewildered. One nun in particular kept shaking her head unbelievingly at Slim Jim juggling, the teeth dropping act causing a near riot. Tommy was a great hit with his Irish songs and stories. After the show the nuns came over to us for a chat they were like a mob of parrots wonderfully cheerful after their experiences with the Japs.

It was good having the whole unit together again after six weeks. Arrangements for us to move to a special Amenities camp nearby had been afoot for days and on the Tuesday we moved in to the grounds of the Rabaul Hotel which was just on the other side of GDD. The Rabaul Hotel was a complete wreck but must have been a very nice place pre-war. Huge underground tanks were still intact but overgrown with vines and weeds; hibiscus and frangipani also grew in profusion. Every morning, except Sunday, one member of the three Amenities units had to go up to the Jap compound to collect twelve Nips so that it became our turn every three days. The man whose turn it was had to wake up at 5.30am, march up to the compound about a mile away, collect the Nips, march them back and send four to each of the three units. They had their own food and had to be marched back again at 5.30 pm. I only had to do the job once, staggered out of bed and along to pick up the Japs who were standing behind a numbered post. Their corporal saluted me, I said “come in Charlie!” and off they trudged down the road with me in the rear, real Digger type, rifle slung over my shoulder to stop any funny business that may crop up. Lucky for me that nothing did, as my rifle was bare of bullets!

Douglas, Ron and Slim Jim did a grand job of the Holy Tent.1 I gathered a lot of ferns, lilies, pawpaw etc. and made three nice gardens in the front of the tent, which of course brought a lot of ridicule for me, which deepened when I carried dozens of buckets of small stones from rubble heaps and foyer of the hotel and made two paths between the gardens to the tent. It looked very nice and kept the dust down well. The wind used to blow through the tent wildly as we had the sides raised about three feet from the ground so to counteract the wind. Douglas put a little light outside the entrance; some wag tried to paint the globe red, but I caught him at it, then Fred wrote ‘LADIES’ on the entrance. A couple of caustic remarks from Douglas and me caused him to rub it out. On a concrete floor opposite the rec hut, Douglas erected a couple of tarpaulins and the piano was placed there; this became known as the ‘Conservatorium’.

We eventually got the same four Nips every day and they certainly had an easy time. It was rather difficult trying to be aloof and we often found ourselves chatting to them in pidgin and sign language. With home going getting very near, all musically minded boys began to practice madly for post war efforts. Weird noises issued from under trees, in foxholes, in trucks, and wherever possible to practice in peace: to themselves, the rest of us stopped our ears or assumed different attitudes.

First show was given to 11 Brigade and, as their stage was entirely unsuitable, we erected our own stage next to it. A team of Japs was brought along to do the work under direction from our lads. The Nips were willing, especially when we got the same ones every day we showed. I found them hanging out the wardrobe for me on a couple of occasions and when I’d start ironing they’d all want to help, expressing admiration for the colours of the shirts and dresses. A couple even wanted to iron for me!

Nothing of much importance occurred at the seven shows; the New Year’s Eve one was given to a unit we had played to in Northern Territory. The stage was erected on the edge of the playing field that looked as if it was constantly under water. Our dressing rooms were placed over waterways and what have you. I ran around and got pieces of wood and tin to build over them just in case, for when it rains in New Britain, it rains! Comes straight down and floods everything in a few minutes. Never have I seen such rain and the lightning was awesome to see. I often woke in the night to find it raining; often too we would wake to find ourselves rocking in our beds and to hear the utensils of the GDD kitchen swaying as the ground heaved underneath. Why we didn’t vanish into the tunnel underneath I don’t know. A subsequent letter from Billy Chee-Shin-Ching informed me that our camp finally did go underground under persuasion of yonder volcanoes.

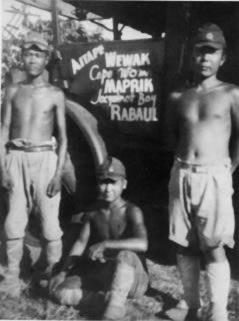

A lot of us had taken courses with Army Education Service as soon as we arrived in Rabaul; my first lesson arrived 8 months later! Jap swords were being distributed to units, one to every three men, we got a few, so names were put in to a hat; I got the better of the second issue to us. Several natives came up to the camp to do washing or to bring fruit. We were not due to sail till 28 January so had plenty of time to prepare our gear and selves. The Nips polished the trucks and generator till they absolutely shone. Also, got Jack Romeril to paint the names of all our ports of call on the doors of his stage truck, but alas at the last moment we had to leave all vehicles behind for other parties to use. I would go for long walks every night after tea, sometimes just round and round the square, or up and down the main road, but I liked best to sit on the wharf till it got dark2.

On the Saturday before we left Rabaul, a sports meeting was held on a big clearing between the camp and the hills. This had once been an airstrip so it was solid, but evidently the one nearer the volcano was more useful. Preparations had been in hand for weeks to make a race track and grandstands. I didn’t go to it but saw one of the races from a distance. The ANGAU band played and marched during the morning and in the afternoon a regatta was held on the harbour. I didn’t go to this either, but did go to the sing song held at night on the course. Colourful and ingenious costumes were worn by the dancers, all made of course, and they danced on monotonously while the ‘orchestra’ banged wooden blocks and chanted the same tune over and over again. When exhausted, the dancers would retire for a rest and a fresh lot would come on. One troupe had white circles painted on arms legs and bodies giving them the appearance of having football jerseys and socks on.

Georgetown Victory was to be our ship and on the 27th we made ready to leave, but as a disturbance was being held on board we had to settle in our tents again. Discarding of old junk had been going on for weeks among us and now that our last days had arrived, we just handed a well-equipped camp over to the new unit. After breakfast, Billy Chee-Shin-Ching came along to make his farewells and left loaded with clothes plus several hats on his head and several pairs of boots hanging over his arm. Then straight after lunch, we gathered the rest of our gear together and to the wild waving of caps from our yellow bellies, we left Amenities camp to the mercies of the musical comedy company.

We didn’t have to wait too long to get aboard a barge, then we pulled away from New Britain and so out to the Georgetown Victory where it lay anchored. Literally thousands seemed to be going aboard, it was said that 500 more than capacity were taken aboard and I quite believe it. We all staggered up the gangplank and then had to go down two decks to a hold where iron beds were built three high. Crowds kept coming down everyone was jumbled, it was dark and the heat terrific, we could hardly breathe.

With the coast of Queensland in sight we had to go through a very rude medical examination and the next morning we anchored outside the mouth of Brisbane River for a few hours, then at 1 pm began to slowly, oh so slowly, move up to the city. Everyone was strangely quiet, even when the factories blew their whistles to greet us, people rushed to doors and windows to wave, little boats fussed about, sirens hooted and a general noise went on till we eventually came to Hamilton Wharf where the Queensland L of C Brass Band played rousing tunes while a crowd of people were held back at the gate of the wharf. The Concert Party odds and sods piled in to a truck and were taken by a back route to Chermside arriving at 6 pm. A beautiful meal was given us and we were put in to a hut, where, after a wash up, we all went in to Brisbane arriving at 8. I had been looking forward to a lovely hot shower at the Union Jack club, but when I peeled off and turned on the shower it was icy cold! We had to report to Chermside every morning till we finally left for Sydney on the following Saturday.

Japanese prisoners with stage truck

Notes

Douglas Zanders was a New Zealander studying the piano in Melbourne when war broke out. In 1946 he returned to his home town of Christchurch, and then in 1952, with my mother and me, immigrated to England, where he subsequently spent many years as a well-respected piano teacher. I occasionally asked him about his war years, but he did not give much away except to talk about his piano falling apart in tropical rainstorms, or the irreverence of his Aussie mates. I became more interested in his story during the last years of his life (he died in 2012) and discovered Michael Pate’s book An Entertaining War (Dreamweaver Books, Sydney, 1986). This describes the Australian Army concert parties in great detail and led me to Frank Lamprell’s personal memoirs.

1. From Frank Lamprell’s account at Hayes Creek, Australia: Ed, Douglas and myself were given a tent to ourselves which in usual style we soon made very comfortable. As none of us drank and only Ed smoked, and swearing was ‘out’ our tent was christened the ‘Holy Tent’, but was always, right up to the disbandment of the unit in 1946, considered the tidiest and best tent in the unit.

2. Douglas must have explored the local area as well; he wrote down the words and music for several native songs in Bai village (see illustration above).