PNGAA Library

The day of the Kundus: Pat Poircuitte (née Spence)

I read with interest the article in the last edition of Una Voce, "Kiap Tribute Event", but of more interest to me was the article taken from the speech Nance Johnston made regarding the life and times of the wives of the Kiaps. It dealt with the trials and difficulties of everyday living, especially those crises involving children. All this prompted me to put pen to paper (or fingers to computer) and describe my own parents' initiation into life in the tropics. The following story is part of our family history, told me by my mother.

My parents, Albert and Louise Spence (Bert and Lou) together with six-week old son, Richard Albert (and always to be known as Dick) arrived in Rabaul from Sydney in 1926. Dad had taken a position as manager of a copra plantation (probably Kurakakaul) and had to disembark at Rabaul to wait for the government trawler to take them on the last leg of their journey to the east coast of New Britain. No roads in those days. As the trawler would take a few days before it got to Rabaul, mum spent that time stocking up on tinned food and milk as a precaution against shortages at the house.

Finally the little party set off for what was to be "best part of a day's voyage" but which actually turned out to be two and a half to three days on the water. Some malfunction of the trawler motor caused it to shut down and they had to drift until help came. There was no problem with food, but exposure in an open boat, for a tiny baby, caused him to develop a nasty throat infection and he became steadily worse. When they finally tied up at the wharf, and were escorted to the house, he was, in fact, a very ill baby.

I use the word "house" but it was really only a shack, though standard accommodation on plantations in that era: bamboo walls, pitpit flooring (split wood) and Kunai Grass roof. As the baby could scarcely breathe by that time, it was realised that unless medical help came, he would not survive, but of course they were miles from help.

As has been the custom for many centuries, indigenous people have been able to give and receive news by Kundus (bush telegraph) relaying messages from village to village. The workers on the plantation were no exception, and a young doctor, Ray Cilento (later to be known as Sir Raphael Cilento), who happened to be at a mission station on his rounds, heard of the trouble and began his errand of mercy. He decided to perform a tracheostomy on the baby. Even though he was so very young, there was really no option. But that necessitated waiting until the throat stricture reached a certain point and it was at this time that a message reached the doctor, again through Kundus, that a patient in childbirth at the mission would not survive without his help. So the good doctor left all the necessary medical instruments, sedation, etc, laid out on the table with verbal and written instructions on how my father was to perform the operation on his six-week old son. And so the waiting began.

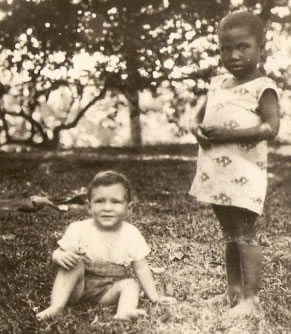

One can only begin to imagine the horrors and fears that must go through the minds of parents in this situation. But the gods (or fate) must have looked down kindly on this pitiful domestic drama, for within two hours, the swelling decreased, as did the temperature, and the child breathed normally, as no doubt did my father, having been released from such a terrible responsibility. Dick gradually regained his strength and the Kundus relayed the good news yet again to the doctor who returned a few days later to check the patient out and to retrieve his instruments. My parents were told that Dick should not be allowed to put any pressure or strain on his throat, as in screaming, etc, for a couple of years, and for this reason, the child's every wish and whim was granted by his doating Meri and because that particular area was so isolated, there were no other European children with whom he could play. He grew up trilingual, speaking fluent "place talk", pidgin and bad English. Mum said he was probably the most spoiled child on the island. But he grew from "L'enfant terrible" to become a fine man, respected, admired and loved by all, especially the very many students with whom he worked in his position as Department Head of the Faculty of Civil Engineering at Sydney TAFE.

When my parents moved into Rabaul, they often came into contact with Doctor Cilento who said he'd never forget Dick, the mission mother and child or the day of the Kundus.